Under a naive reading of Malthusian theory, yield (the amount of food or fodder produced per unit area) should have improved after the Black Death: a lower population abandoned marginally productive lands and kept the better yielding ones. Furthermore, the increased ratio of livestock to arable acres should have improved fertilization of the fields, as more nutrients and especially nitrogen moved from wastes (wild lands) and pastures to the arable.

But while marginal lands were indeed abandoned (or at least converted from arable to pasture), and the livestock/arable ratio indeed increased, it's not the case that yield improved after the Black Death. In fact, the overall (average) yield of all arable probably declined slightly, and the yields of particular plots of land that were retained as arable usually declined quite substantially. Yields declined and for the most part stayed low for several centuries thereafter. Other factors must have been work, factors stronger than the abandonment of marginally productive lands and the influence of more livestock on nutrient movement.

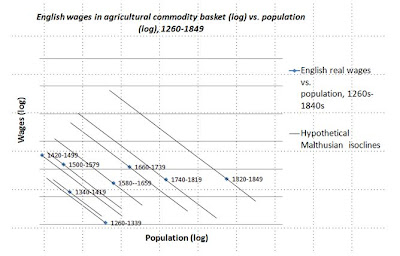

Per capita agricultural output (vertical axis) vs. population density (horizontal axis) in England before, during, and after the Black Death and through the agricultural revolutions of the succeeding centuries.

Per capita agricultural output (vertical axis) vs. population density (horizontal axis) in England before, during, and after the Black Death and through the agricultural revolutions of the succeeding centuries.The main such factor is that increasing yield without great technological improvement requires more intensive labor: extra weeding, extra transport of manures and soil conditioners, etc. Contrariwise, a less intensive use of land readily leads to falling yield. After the Black Death, labor was more expensive relative to land, so it made sense to engage in a far less intensive agriculture. The increase of pasture and livestock at the expense of the arable was a part of this. But letting the yield decline was another. What increased quite dramatically in the century after the Black Death was labor productivity and per capita standard of living (see first three points on the diagram, each covering an 80-year period from 1260 to 1499).

Indeed, the whole focus in the literature on improvements in "productivity" as yield in the agricultural revolution has been very misleading. The crucial part of the revolution, and the direct cause of the release of labor from the agricultural to the industrial and transport sectors, was an increase in farm labor productivity: more food grown with less labor. Over short timescales, that is without dramatic technological or institutional progress, farm labor productivity was inversely correlated with yield for the reasons stated. Higher labor productivity, certainly not higher yield, is what distinguished most of Europe for example from East and Southeast Asia, where under intensive rice cultivation, and abundant rain during warm summers, yield had long been far higher than in Europe. Per Malthus, however, population growth in these regions had kept pace with yield, resulting in a highly labor-intensive, low labor productivity style of agriculture, including much less use of draft animals for farm work and transport.

The bubonic plague was spread by rodents, who in turn fed primarily on grain stores. This also had a significant impact on agriculture, because grain-growing farmers and grain-eating populations were disproportionately killed and people fled areas that grew or stored grain for regions specializing in other kinds of agriculture. In coastal regions like Portugal there was a large move from grain farming to fishing. In Northern Europe there was a great move to pasture and livestock, and in particular a relative expansion of the unique stationary pastoralism that had started to develop there in the previous centuries, both due to the relative protection of pastoralists from the plague and the less labor-intensive nature of pastoralism after land had become cheaper relative to labor.

A final interesting effect is that the long trend from about the 11th to the 19th century in England of conversion of draft animals from oxen to horses halted temporarily in the century after the Black Death. The main reason for this was undoubtedly the reversion of arable to pasture or waste (wild lands). Oxen are, to use horse culture terminology, very "easy keepers". As ruminants they can convert cellulose to glucose for energy and horses can't. Oxen, therefore, became relatively cheaper than horses in an era with more wastes and less (or at least much less intensive use of) arable for growing fodder. This kind of effect occurred again much later on the American frontiers where there was a temporary, partial reversion from horses to oxen as draft animals given the abundance of wild lands relative to groomed pasture and arable for growing fodder. For example the famous wagon trains to California and Oregon were pulled primarily by oxen, which could be fed much better than horses in the wild grasslands and arid wastes encountered. However in England itself, the trend towards horses replacing oxen, fueled by the increasing growth of fodder crops, had resumed by 1500 and indeed accelerated in the 16th century, playing a central role in the transportation revolutions of the 15th through 19th centuries.