The vast nation, the Chinese Empire, sent abroad vast naval flotillas -- the Zheng He fleets. The main purpose of these fleets was not to develop trade, nor to protect trade, nor even to conquer. Instead, the main purpose was simply to display the glory of the Chinese Empire, which as everyone already knew was indeed the most glorious and powerful empire on the planet. A quite secondary purpose was to collect tribute, which came nowhere near the levels needed to fund the fleets.

Size of a Zheng He "treasure ship" vs. a typical Portuguese or Spanish caravel (here Columbus' Santa Maria).

These state fleets operated completely independently of the vibrant private Chinese merchant fleets that traded not only off China with Japan and Korea and the Philippines, but in Indonesia, Indochina, India, and as far as the east coast of Africa. Zheng He did not help to either protect, expand, or otherwise enable this trade. Instead Zheng He, a eunuch and master bureaucrat of the Emperor, sailed his vast fleet as far as Africa accomplishing little more than showing off the glory of the Emperor and collecting exotic animals for his amusement.

All it took was a political change for the bureaucracy to realize that these expeditions were far too expensive and ultimately pointless. But, as often occurs with politics, the Emperor overreacted and banned not only Zheng He's "treasure fleets," but also the productive trade of the Chinese merchants. The last "treasure fleet" returned in 1433 and China soon withdrew on itself. A million-yuan giraffe, brought back to China from East Africa by a Zheng He flotilla in 1414 (click to enlarge). Not the most cost-efficient zoo acquisition, but the Emperor's ships were bigger and grander than anybody else's! In the same year, on the other side of the planet, the Portuguese using a far humbler but more practical fleet took the strategic choke-point of Ceuta from the Muslims.

A million-yuan giraffe, brought back to China from East Africa by a Zheng He flotilla in 1414 (click to enlarge). Not the most cost-efficient zoo acquisition, but the Emperor's ships were bigger and grander than anybody else's! In the same year, on the other side of the planet, the Portuguese using a far humbler but more practical fleet took the strategic choke-point of Ceuta from the Muslims.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, a tiny nation of fishing villages and small-time crusaders set out on a different path. Assisted by navigators and investors from other parts of Europe, the Portuguese embarked on a pay-as-you go path of conquest and trade. They focused on conquering strategic points that allowed them to control, tax, protect, and enable trade. They enforced the property rights of their allied merchants and otherwise enabled the commercial institutions by which that trade could flourish.

The first little conquest was Ceuta, on the African side of the Straights of Gibraltar, the strategic choke point of the Atlantic-Mediterranean shipping routes. In 1414, at the height of the Zheng He expeditions, Prince Henry ("the Navigator") of Portugal conquered Muslim Ceuta for the Christians. Having gained this crucial strategic advantage over their Muslim and Genoan rivals, Portugal went on to conquer and settle several Atlantic island chains that had been discovered by the Genoans, including the Canaries and the Azores. The Portuguese also followed the older Genoese missions down the west coast of Africa.

At each step down Africa, the Portuguese set up trading stations. They traded European goods ranging from weapons to Venetian glass beads (used by many Africans as money and jewelry) for gold, slaves, and a variety of exotic products. At the same time the Chinese Empire was persecuting its merchants, banning them from trading overseas, the Portuguese were slowly expanding their trading posts down the coast of Africa, paying for their explorations as they went by setting up new and lucrative businesses.

Each expedition pushing farther south was a humble affair involving tiny numbers of small ships. Soon after the middle of the century, the Portuguese learned by repeated experience how to navigate out of sight of the (northern) Pole Star. Using this knowledge they made their way down the west coast of Africa in the southern hemisphere. Then they did what no Arab, Chinese, or Indian navigator had apparently done from the other direction. In 1488 Bartolemeu Dias' tiny fleet of caravels sailed around the southern cape of Africa and into the Indian Ocean. Four years later Portugal's neighbor Spain sent the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus to Asia from the other direction, but Asia turned out to be much farther west than Columbus predicted and America sat in between.

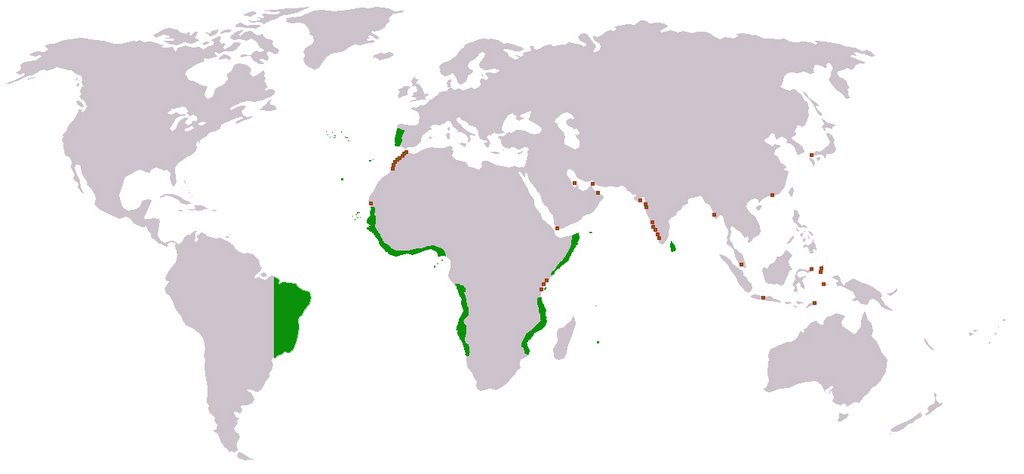

Extent of the Portuguese maritime empire by the mid 16th century (click to enlarge). Controlled territory in green; forts and trading colonies in red. By stark contrast, China with its vast wealth, advanced civilization, and giant fleets failed to sail around Africa to set up trading posts on the west coast of Africa or Europe.

Using its now mature experience in open-seas navigation and advanced European technologies such as the cannon, as well as its good sense of affordable yet effective fighting and trading ships, subsequent Portuguese naval fleets soon conquered the main strategic choke points of Middle Eastern and Asian trade: Hormuz, Malacca, and others. Rather than ignoring merchants, they focused on controlling and enabling trade. They weren't out to show off the glory of Portugal; instead they created it. They invited investors from many other parts of Europe to send trading fleets. Trading between different Asian ports and trading European silver for exotic Asian goods both proved quite lucrative. By the early 16th century, the Portuguese had revolutionized navigation and had conquered the main trade routes of the world. Instead of Chinese fleets conquering Ceuta and Gibraltar and setting up trading posts in London and Lisbon, it was Portuguese fleets that set up trading colonies in India, Indonesia, Japan, and China. Soon other small European nations were to follow.

When it comes to the "final frontier" of space, it seems to be so far the West that has stepped into China's old shoes. What did Apollo return but glory and a handful of rocks? We proved that our socialists, if funded by taxing capitalists, could beat their socialists funded by socialists. Did such proof of bureaucratic glory really require 1% of our GDP over several years?

Apollo has been followed by several more white elephants that have much more to do with showing off the power and glory of federal bureaucrats than with military advantage or practical business. The space shuttle was originally promised to cost $36 million per flight (in today's dollars). It was supposed to greatly reduce the cost to space and thereby give rise to "space-based civilization." NASA predicted that we would have bases on Mars by the year 2000, and a generation of boys dreamed of growing up to be astronauts who traveled across the solar system.

A billion-dollar rock made of anorthosite, a very common mineral on earth as well as on the moon. But we got there first, and our rocket was bigger than theirs!

In fact the Shuttle ended up costing $1.5 billion per flight, over forty (40) times the promised price even when adjusted for inflation . The space station announced in the early 1980s and promised to be completed within a decade. But the first module was not launched (to be assembled into the greatly designed-down form of the International Space Station) until 1998. And just NASA's portion of the cost has exceeded its estimated cost for the entire program when it was first announced.

Past and current proposals for Moon and Mars bases are also nothing more than the same kind of dramatic white elephants: they have no realistic prospects of military advantage or practical business. NASA is still stuck on Werner Von Braun's sixty-year-old science fiction scenario of "space stations" and "bases" that have almost no practical use beyond showing off the power of federal bureaucrats to spend vast sums of money in dramatic ways.

There is a thread of space development that more closely resembles the pay-you-go methods of Portugal and other successful explorers and developers of frontiers. These involve launching useful satellites into orbit for communications and surveillance. As with the Portuguese, these serve both military and commercial purposes. They are not just for show. Spinoffs of these spacecraft form the flotilla of small unmanned spacecraft we have sent to by now explore all the planets of the solar system, as well as several comets and asteroids. The succesful Hubble telescope is a spinoff of the U.S. National Reconaissance Office's spy satellites. And environmental satellites have revolutionized weather prediction and climate study on our home planet. Recently, space tourism with suborbital rockets has demonstrated a potential to develop a new thread of pay-as-you-go space development largely unrelated to the prior gargantuan manned spaceflight efforts.

The Zheng He and NASA style of frontier-as-PR, where the emphasis is on showing the glory of the government, is a recipe for failure in the exploration and development of new frontiers. It is in sharp contrast to the pay-as-you go method by which tiny Portugal conquered the world's oceans, exemplified today by the practical unmanned satellites of the commercial and military efforts. It is by these practical efforts, that fund themselves by commercial revenue or practical military or environmental benefit, and not by glorious bureaucratic white elephants, that the successful pioneers will, in good time, explore and develop the solar system.

Perhaps it should be left to private firms to develop space. If so, what should NASA's role be?

ReplyDeleteThe most credible justification for NASA is to create "public goods" -- things that private companies would tend to create much less of because they could not recoup much of the value in the form of revenues and profits.

ReplyDeleteBy this view the most valuable part of NASA is that part that which produces science and engineering data that have widespread benefits in the aerospace industry, as well science that adds to our understanding of the earth's environment and basic theory.

Examples of things that are not public goods but that NASA is often tempted to engage in: trying to prematurely establish an industry by subsidizing it (because the shape of the future is best discovered by competitive experimention rather than planning)and things mainly done to glorify the government itself, as described in my article.

Two great examples of the small initiative are the work of www.spacex.com and the writing of Robert Zubrin on going to Mars... The small initiative is winning, and NASA is even starting to inspire the small player with the Centennial Challenges, based off of the X PRIZE. A change is in sight, even within NASA.

ReplyDelete