We have seen that U.S. Rep. David Crockett, later a hero of the Alamo, argued passionately against the propriety and constitutionality of federal charity. Crockett told his fellow Representatives that taxpayer money was "not yours to give."

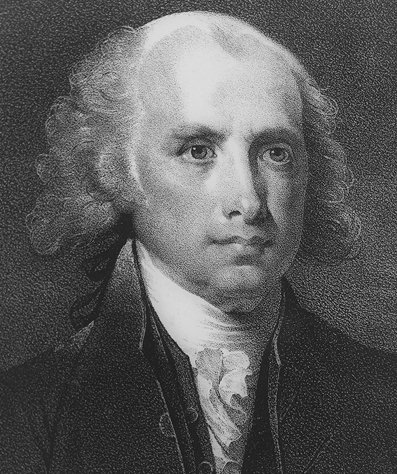

During the first several decades after the U.S. Constitution was enacted, constitutional issues were debated and decided far more often in Congress than in the Supreme Court. Crockett was part of a long line of early and eminent Congressional constitutionalists who argued against the constitutionality of federal charity. Another was James Madison, one of the main drafters of the Constitution as well as one of its main proponents in the Federalist Papers. Opposing moderate Federalists and Republicans were were radical Federalists who argued following Alexander Hamilton for practically unlimited federal powers. According to Crockett, Madison, and many others, Congress had no power under any clause of the Constitution to allocate money for charity, except when such charity was necessary and proper (using a fairly narrow construction of that phrase) for implementing an enumerated Congressional power such as funding and governing the armed forces, paying federal debts, executing the laws, or implementing treaties.

David P. Currie's book The Constitution in Congress chronicles these early constitutional debates and is a must read for constitutional scholars. It contains debates by many House members (including James Madison, Elbridge Gerry, and other founders and drafters) on the constitutionality of many different kinds of legislation. Currie cites the Annals of the early Congress which are now online. Currie discussses the following two debates on federal charity:

(1) In 1793, a number of French citizens were driven out of the French Colony of Hispaniola (now Haiti), landed in Baltimore, and petitioned Congress for financial assistance. Rep. John Nicholas expressed doubt that Congress had the constitutional authority "to bestow the money of their constituents on an act of charity."[1] Rep. Abraham Clark responded that "in a case of this kind, we are not to be tied up by the Constitution." [2]. Rep. Elias Boudinot, another radical Federalist, argued that the general welfare clause authorized this kind of spending.[3] Rep. James Madison resolved the debate by observing that the U.S. owed France money from the Revolutionary War. Madison disagreed with the radical Federalist interpretation of the general welfare clause and argued against setting a dangerous precedent for open-ended spending. Congress could, however, provide money to the French refugees in partial payment of these debts, and thus constitutionally under Congress' Article I powers to pay federal debts.[4]

(2) The second opportunity to debate the constitutionality of federal charity occurred when a fire destroyed much of the previously thriving city of Savannah, Georgia in 1796. The fire was referred to as a "national calamity." Rep. John Milledge related how "[n]ot a public building, not a place of public worship, or of public justice" was left standing. Rep. Willaim Claiborne again raised the radical Federalist argument that the measure to help fund the rebuilding of Savannah was constitutional under the general welfare clause.[5] Reps. Nathaniel Macon[6], William Giles[7], Nicholas[8], and others argued that allocating federal funds to relieve Savannah would violate the Constitution, since such charity was not authorized by any enumerated power in the Constitution. "Insurance offices," not the federal government, were "the proper securities against fire," according to Macon.[8] Rep. Andrew Moore argued "every individual citizen could, if he pleased, show his individual humanity by subscribing to their relief, but it was not Constitutional for them to afford relief from the Treasury."[9] The measure to provide relief to Savannah from federal tax dollars was then defeated 55-24 [10].

[1] David P. Currie, The Constitution in Congress, citing 4 Annals at 170, 172.

[2] Id. citing 4 Annals at 350.

[3] Id. citing 4 Annals at 172.

[4] Id. citing 4 Annals 170-71.

[5] Id. pg. 222 citing 6 Annals 1717.

[6] Id. citing 6 Annals 1724.

[7] Id. citing 6 Annals 1723.

[8] Annals 1718(online)

[9] Id.

[10] Currie citing 6 Annals 1727.

Here is a direct link to the Annals of Congress. Here is the start of the Savannah debate and here are some of Rep. Macon's comments during the debate.

(n.b. Currie's citations do not necessarily match the page numbers in the online version of the Annals).

Images: Rep. James Madison (top), Rep. Nathaniel Macon (bottom).

3 comments:

last 2 posts are outstanding. I am using them for ammo over on the Ed schultz forums.

http://edschultz.invisionzone.com/index.php?s=9c1431d98cf57f4b75cab830060af984&showforum=11

btw I go under the name cornopean.

I love the Internet! It makes life more difficult for those who make outrageously distorted claims about the past when honest people have access to resources like this. Keep up the good work!

Post a Comment