The

long reach of habeas corpus was reaffirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, in 2004, when it ruled that U.S. citizens detained in Guatanamo Bay, a U.S. military base on long-term lease from Cuba, were on U.S. territory and therefore have a right to plea to a U.S. federal court for

habeas corpus and thereby enforce certain minimal liberty rights under the Due Process Clause. The companion case,

Rasul v. Bush, declared that aliens (non-citizens) held at an overseas U.S. military base also have this right. However, recently passed legislation, the Military Commissions Act, has

suspended habeas corpus protection for all aliens, even the tens of millions of aliens visiting or residing inside the United States proper. It also jeopardizes many of the legal protections U.S. citizens have against arbitrary detainment once we have invoked

habeus corpus.In

Hamdi Justice Scalia, unusually joined by Justice Stevens, quoted William Blackstone's 18th century legal treatise, parts of which had also been quoted by Alexander Hamilton in

Federalist #84:

"Of great importance to the public is the preservation of this personal liberty: for if once it were left in the power of any, the highest, magistrate to imprison arbitrarily whomever he or his officers thought proper ... there would soon be an end of all other rights and immunities. ... To bereave a man of life, or by violence to confiscate his estate, without accusation or trial, would be so gross and notorious an act of despotism, as must at once convey the alarm of tyranny throughout the whole kingdom. But confinement of the person, by secretly hurrying him to gaol, where his sufferings are unknown or forgotten; is a less public, a less striking, and therefore a more dangerous engine of arbitrary government. ...

"To make imprisonment lawful, it must either be, by process from the courts of judicature, or by warrant from some legal officer, having authority to commit to prison; which warrant must be in writing, under the hand and seal of the magistrate, and express the causes of the commitment, in order to be examined into (if necessary) upon a habeas corpus. If there be no cause expressed, the gaoler is not bound to detain the prisoner. For the law judges in this respect, ... that it is unreasonable to send a prisoner, and not to signify withal the crimes alleged against him." 1 W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 132-133 (1765) (hereinafter Blackstone).

Scalia added:

It is unthinkable that the Executive could render otherwise criminal grounds for detention noncriminal merely by disclaiming an intent to prosecute, or by asserting that it was incapacitating dangerous offenders rather than punishing wrongdoing. Cf. Kansas v. Hendricks, 521 U. S. 346, 358 (1997) ("A finding of dangerousness, standing alone, is ordinarily not a sufficient ground upon which to justify indefinite involuntary commitment").

Both Scalia and Stevens held that this applied to military detentions of U.S. citizens as much as to imprisonment by civilian courts. However Scalia, but not Stevens, made a strong distinction between U.S. citizens and aliens. "Citizens aiding the enemy have been treated as traitors subject to the criminal process," and thus when imprisoned entitled to invoke the federal courts via

habeas corpus.The Great Writ has been often been suspended in areas and periods of warfare, allowing armies to capture enemies

en masse without incurring legal overhead, but such suspensions have often led to unjust deprivations of liberty. Liberty, as well as life, property, and truth, is a common casualty of war. Without

habeas corpus severe political oppression and deprivation of liberty through the practice of

disappearing becomes all too easy.

Blackstone wrote about the conditions under which the writ might constitutionally be suspended:

"And yet sometimes, when the state is in real danger, even this [i.e., executive detention] may be a necessary measure. But the happiness of our constitution is, that it is not left to the executive power to determine when the danger of the state is so great, as to render this measure expedient. For the parliament only, or legislative power, whenever it sees proper, can authorize the crown, by suspending the habeas corpus act for a short and limited time, to imprison suspected persons without giving any reason for so doing... . In like manner this experiment ought only to be tried in case of extreme emergency; and in these the nation parts with it[s] liberty for a while, in order to preserve it for ever." 1 Blackstone 132.

Among other constitutional problems with

the recently passed legislation, the Military Commissions Act, suspending habeas corpus for aliens, is that it has done so until repealed by Congress, rather than "for a short and limited time." It's also absurd to argue, as some have, that the U.S. currently in a state of "invasion" or "rebellion" as required by the Constitution:

The privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it. Art. I, §9, cl. 2.

In

Eisentrager v. Forrestal, the Court had held that German citizens captured in China during World War II and imprisoned in Germany did not have the right to invoke

habeas corpus in U.S. federal courts. The special conditions quoted in

Eisentrager were as follows: the defendant " (a) is an enemy alien; (b) has never been or resided in the United States; (c) was captured outside of our territory and there held in military custody as a prisoner of war; (d) was tried and convicted by a Military Commission sitting outside the United States; (e) for offenses against laws of war committed outside the United States; (f) and is at all times imprisoned outside the United States." Although

Eisentrager was decided by a court similar to the Court that decided the notorious case of

Korematsu, legitimatizing wholesale confiscation of property and internment in concentration camps of innocents in wartime, it does set at least some minimal bounds on what alien combatants may be arbitrarily derived of their liberty.

As Justice Stevens wrote in his majority opinion in

Rasul: this Court has recognized the federal courts' power to review applications for habeas relief in a wide variety of cases involving Executive detention, in wartime as well as in times of peace. The Court has, for example, entertained the habeas petitions of an American citizen who plotted an attack on military installations during the Civil War, Ex parte Milligan, 4 Wall. 2 (1866), and of admitted enemy aliens convicted of war crimes during a declared war and held in the United States, Ex parte Quirin, 317 U. S. 1 (1942), and its insular possessions, In re Yamashita, 327 U. S. 1 (1946).

Stevens distinguished the facts in

Rasul from those in

Eisentrager:Petitioners in these cases differ from the Eisentrager detainees in important respects: They are not nationals of countries at war with the United States, and they deny that they have engaged in or plotted acts of aggression against the United States; they have never been afforded access to any tribunal, much less charged with and convicted of wrongdoing; and for more than two years they have been imprisoned in territory over which the United States exercises exclusive jurisdiction and control.

In concurrence, Justice Kennedy distinguished the Guantanamo Bay detentions from those in

Eisentrager as follows:

The facts here are distinguishable from those in Eisentrager in two critical ways, leading to the conclusion that a federal court may entertain the [habeas corpus] petitions. First, Guantanamo Bay is in every practical respect a United States territory, and it is one far removed from any hostilities....The second critical set of facts is that the detainees at Guantanamo Bay are being held indefinitely, and without benefit of any legal proceeding to determine their status. In Eisentrager, the prisoners were tried and convicted by a military commission of violating the laws of war and were sentenced to prison terms. Having already been subject to procedures establishing their status, they could not justify "a limited opening of our courts" to show that they were "of friendly personal disposition" and not enemy aliens. [citation omitted] Indefinite detention without trial or other proceeding presents altogether different considerations. It allows friends and foes alike to remain in detention. It suggests a weaker case of military necessity and much greater alignment with the traditional function of habeas corpus. Perhaps, where detainees are taken from a zone of hostilities, detention without proceedings or trial would be justified by military necessity for a matter of weeks; but as the period of detention stretches from months to years, the case for continued detention to meet military exigencies becomes weaker.

During the debate over the Military Detentions Act some Senators, such as Arlen Specter (R-PA), argued that the

habeas corpus provision of this Act was unconstitutional, but then, pathologically, voted for it anyway. In the early years of the Constitution, it was Congress, not the Courts, who were mainly responsible for making sure legislation stayed within constitutional bounds, and constitutional issues were often debated in Congress and were considered the most decisive issues. Voting for an admittedly unconstitutional Act was a highly irresponsible act. We have a seriously paranoid and unstable situation with Washington D.C. culture and it cannot be predicted how the highly divided Court with two new conservative membes will vote. Not just the Supreme Court, and not just the Executive, but all U.S. citizens, including Congress, are responsible for obeying the Constitution and ensuring that it is obeyed by our leaders.

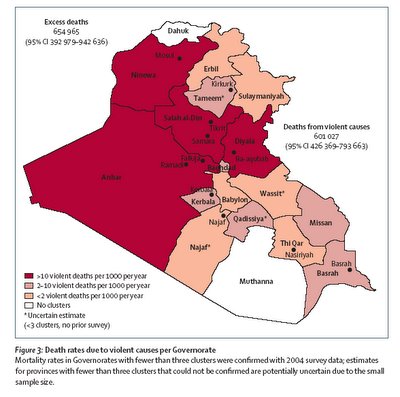

A sample of 12,801 individuals in 1,849 households and in 47 geographical locations shows that the death rate in Iraq increased from 5.5 people thousand people before the U.S. invasion to 13.3 per thousand after. This is almost entirely due to a vast increase in the number of violent deaths.

A sample of 12,801 individuals in 1,849 households and in 47 geographical locations shows that the death rate in Iraq increased from 5.5 people thousand people before the U.S. invasion to 13.3 per thousand after. This is almost entirely due to a vast increase in the number of violent deaths.

Symbols are indispensible, but we lost something when symbolic algebra replaced geometry as the main medium of mathematics. My math is quite rusty but I understood these proofs within a few seconds. Via

Symbols are indispensible, but we lost something when symbolic algebra replaced geometry as the main medium of mathematics. My math is quite rusty but I understood these proofs within a few seconds. Via